Kachemak CoastWalk

Since 1984, the Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies has coordinated an annual effort to monitor Kachemak Bay, located on the lower Cook Inlet. Volunteers choose a section of beach to walk during the three weeks of CoastWalk and collect observational data of marine, bird, and animal life, signs of human use and impacts, and any noticeable changes to their stretch of beach. Active stewardship through the associated beach clean-ups has resulted in the removal and disposal of tons of trash and marine debris.

This grassroots program came from our local citizens concerned about the changes they were witnessing along our shorelines. Alaska’s beaches are some of the most dynamic on earth and thus are excellent for the study of change, both in response to small and large-scale natural forces and the activities of people who are drawn in increasing numbers to our shoreline for recreation, residential, commercial, and industrial activities. CoastWalk is here to ensure that our coasts are kept in a state that will benefit all of their residents.

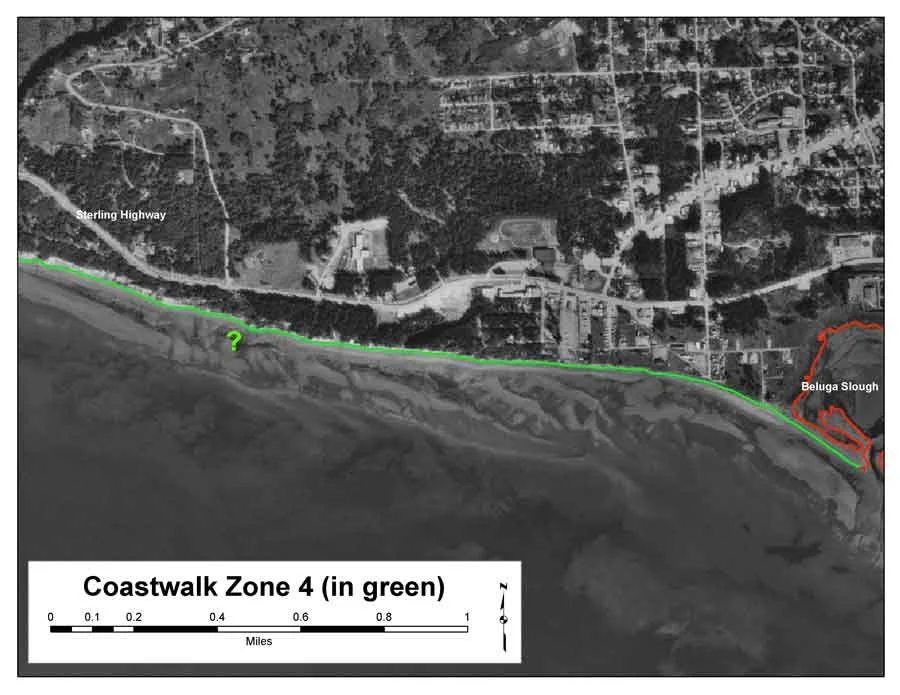

CoastWalk Zones

CoastWalk volunteer groups sign up for a particular zone within Kachemak Bay. A CoastWalk Kick-off meeting is typically held at our Headquarters in early September to coordinate efforts throughout the month. CoastWalk volunteers help complete the CoastWalk Data Sheet, the Biodiversity Survey, the Alaska-Specific Marine Debris Form, and the Ocean Marine Debris Form. After the clean-ups, our team gathers and summarizes the results in annual reports.

Since 1984, CoastWalk has been an annual effort to clean Kachemak Bay’s beaches and collect critical data on marine debris in Alaska. This year we’re thrilled to have Surfrider Kenai Peninsula as a CoastWalk partner. 2025 clean-ups and auxiliary events will be listed below:

Schedule:

2024 Statistics:

Pounds of debris removed from Kachemak Bay beaches: over 2500!

Number of clean-ups: 22

Number of volunteers: 450

Thank you all for your help to keep our coastlines clean and contribute critical data to about debris movement in Alaska.

Coastal Monitoring Resources

Find everything you need to set up a coastal monitoring program on the Alaska coastline. Browse our Activity Guides for volunteers and students (grades 4-12) and collected resources that will be essential to putting together your own monitoring program.

The Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies is partnering with Gulf of Alaska Keeper on a 3-year marine debris removal project at Montague Island.

Learn more about the project and how to volunteer for these cleanups.

FAQs

What is marine debris?

Marine debris is defined as human-made, solid materials that enter our waterways either directly (such as through dumping) or indirectly (such as through washing out to sea via a river or stream). Marine debris includes both biodegradable items and non-biodegradable items.

Why is marine debris more of an issue today than it was in the past?

For thousands of years, marine debris was composed primarily of readily biodegradable items (wooden tools, hemp or linen ropes, cotton or hide clothing). Next, glasses, metals, and paper products were added to the mix. Manufactured glass and metals are not as biodegradable as ancient tools and fibers, but these products are quickly broken down by physical forces and have minimal impacts on the marine environment compared to plastic. Worldwide, about 80% of marine debris is now made up of plastic items. This plastic debris – and other types of marine debris come from four main sources: land based/personal- use items, marine industries and recreation, container ship spills, and natural disasters.

Non-biodegradable items tend to cause the most problems as marine debris since they persist in the environment. Plastic is more of a problem than glass, not only because it is more prevalent. While glass does not biodegrade, it does break into increasingly smaller pieces and mineralize. Further- more, it is fairly inert (usually doesn’t contain or absorb toxic chemicals), usually sinks, and becomes almost equivalent to a human made rock in the ocean. On the other hand, plastic photodegrades into smaller pieces when exposed to UV light,but these pieces often contain or absorb toxins.

How does marine debris affect ecosystems and wildlife?

Marine wildlife can mistake ingest pieces of marine debris. Marine mammals, fish, seabirds, and sea turtles have been known to mistake pieces of plastic, foam, and other debris as their natural food source. The ingestion of plastic marine debris can lead to internal hemorrhaging, starvation, chocking, and death. More information on ingestion or marine debris by marine animals, especially the Laysan Albatross can be found on the US Fish and Wildlife Service site, here.

Long or circular pieces of plastic can entangle marine animals. This items include commonly used items such as fishing line, nets, ropes, packaging bands, and other items that form a loop and quickly entangle a seal, sea turtle, seabird, fish, or whale. The entangled animal can then die from infection, drowning, or starvation. More information on entanglement of marine mammals in Alaska can be found on the Alaska Fish and Game website, here.

Marine debris movement washing up upon the shore can destroy habitat critical to wildlife's survival. Marine debris, especially large or heavy pieces, can scour, smother, and disrupt both marine and shoreline habitat. Shoreline and near-shore marine habitats along Alaska's coastlines are important areas for many marine mammals, fish species, intertidal invertebrates, bears, moose, and shorebirds. Destruction or disruption of these habitats can lead to a decrease in population sizes, behavioral changes, and offspring success.

Marine debris can act as an invasive species vector. Debris which has spent an extended period of time in the ocean waters can become a vector for introducing alien species to the shoreline where it washed ashore. Species attached to marine debris can survive and travel thousands of miles, make landfall and colonize along a shoreline where that species is not native. These new introduced species, usually very resilient, can out compete local, indigenous species, causing major issues to local fisheries and native ecosystems.

How can we prevent marine debris?

While marine debris is a global issue, individuals can make a difference through both local cleanups and prevention of additional debris from entering local waterways.

The Ocean Conservancy has put together resources on ways to keep our seas trash free. And you can join us on our next CoastWalk to keep Kachemak Bay clean and safe.